Resource Center

We invite you to learn more about our ongoing, and upcoming, work by visiting the resources below

FPWA Testimony

Read the latest testimonies from FPWA’s Policy, Advocacy and Research team.

Blogs

Blogs

December 2, 2024

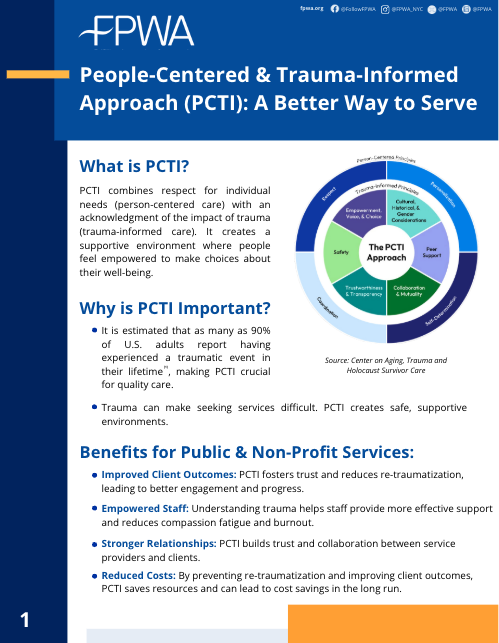

Taking a People-Centered & Trauma-Informed Approach to Improve Programs and Policy

Earlier this year, FPWA worked in partnership with a Capstone Team from New York University’s...

Learn More

Blogs

August 28, 2024

New 2024 Data Highlights Ongoing Economic Disparities Faced By Black People Due to Systemic Discrimination

FPWA today released a data update to our comprehensive analysis “A Look At the March...

Learn More

Blogs

March 19, 2024

Q&A with FPWA Policy Team on What’s at Stake in This Year’s State Budget

March 19, 2024 —Recently, Funmi Akinnawonu, Senior Policy Analyst, and Julia Casey, Policy Analyst, sat...

Learn More

Annual Reports & Financials

Resource Center

How you can Help

FPWA member organizations help low-income New Yorkers meet critical needs, like food, housing, healthcare, and more.

How We Do It

Fostering effective, lasting change requires providing assistance to New Yorkers. But it is also essential to educate on the entrenched structural biases that cause poverty and inequality, and advocate for policy that dismantles it.

Fulfilling the

Promise of

Opportunity

Stay in Touch

Join our network and learn about FPWA events and news.

© 2025 Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.

LEARN MORE

ABOUT FPWA

GET INVOLVED